Monday, July 8, 2013

Wednesday, June 26, 2013

Pewter Basins

An 18th century pewter basin from the Brooklyn Museum collection

https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/803/Basin

Pewter basins/basons (usually rimmed bowls of varied size/capacity) are handy, multipurpose items that those portraying Virginia backcountry folks or militia should consider acquiring. These are fairly lightweight, durable, suitable for fairly hard use (careful with HOT liquids!), and show up in a TON of inventories- even those with a military associations. In 1775 the Williamsburg Magazine was inventoried and inside were "fifty one pewter basons , eight camp kettles" (Journals of the House of Burgesses of Virginia 1773-1776, Volume 13, Pages 223-4 Tuesday, the 13th of June, 15 Geo. iii. 1775 ). These were widely sold in 18th century stores (the previously mentioned New Dublin store in modern Pulaski carried them, as did Hook's New London store, Partridge store in Hanover and etc.) and were usually sold by capacity (ie quarts, pint and etc).

Jefferson county Virginia (which became Kentucky in 1792) probate inventories show a fairly good amount of them in circulation:

http://books.google.com/books/about/Early_Kentucky_Settlers.html?id=whcQpqnUCEcC

Abraham Keller's inventory [possibly Captain of a Company of George Rogers Clark’s Illinois regiment], from 1782 had "3 pewter basons,1 plate & 3 spoons, etc."

His contemporary Robert Travis (also 1782) had "...A parcel of Bar led £ 30 9 Peuter Plates £ 135. 5 Do Basons...". A year prior, William Brashear had "... 9 Pewter plates 2 Dishes, one bason

& Some spoons..." Mary Christy (1782) ties with the Travis inventory for best phonetic spelling of pewter with her inventory's "13 small Puther plates...2 small Do Driper...3... puther basons...1 Small Tea pot...1 small puther bottle." [NB I will cover pocket bottles at a later date].

For further reading (additional pictures of a couple of examples of originals can be seen in the first linked book) :

Pewter at Colonial Williamsburg by John Davis

http://books.google.com/books?id=MwJqjePrg1AC&pg=PA132&lpg=PA132&dq=williamsburg+pewter+bason&source=bl&ots=RaES3OqYdk&sig=OvCb_ceuK9Mjp8NP8GvXUnAAEKw&hl=en#v=onepage&q=williamsburg%20pewter%20bason&f=false

and

The Role of Pewter as Missing Artifact:Consumer Attitudes Toward Tablewares in Late 18th Century Virginia by Ann Smart Martin

http://www.sha.org/CF_webservice/servePDFHTML.cfm?fileName=23-2-01.pdf

Friday, March 15, 2013

Cuttoe Knives Revealed

Cuttoe Knives: A material culture study

by Steve Rayner and Jim Mullins

Trade card of John Cargill, instrument maker at the Saw and Crown, Lomberd street, London. Bears date 1739

In 1775 the intrepid William Cocke rode off alone ahead of his large party of Kentucky settlers on a dangerous 130 mile trip from the Cumberland river. His mission was to warn an advanced party commanded by Daniel Boone in what would become Boonsborough of their pending arrival in order to prevent the settlement from being abandoned in the face of numerous Indian raids.

In order to equip him for this journey he was:

"... fixed ...off with a good Queen Ann's musket, plenty of ammunition, a tomahawk, a large cuttoe knife, a Dutch blanket, and no small quantity of jerked beef."

What was this essential "cuttoe" knife that Mr. Cocke was "fixed...off" with?

One of the most ubiquitous and yet mysterious items from the 18th century is the English manufactured "cuttoe knife". Although mentioned on numerous trade ledgers, account books, newspaper ads and at times even as evidence in murder cases, few real concrete details survive in eighteenth-century documents. Those details that are available are frequently vague and open to interpretation.

One of the problems facing the modern researcher of this item is that eighteenth-century spelling tends to be non-standardized, at times phonetic and generally inconsistent. Compounding this problem is the Anglicization and adoption of the French word for knife; "couteau". At this time there are no known labeled images of a "cuttoe" from the 18th century, but two post eighteenth century references point towards "cuttoe" knives being clasp knives in the cutlery manufacturing center of Sheffield:

A Glossary of Words used in the Neighbourhood of Sheffield 1888.

"Cuteau, sb. a large clasp-knife." p. 58.

and from Sheffield in the eighteenth century - Page 67 Robert Eadon Leader - 1901

"The date 1650 has been assigned as the time when spring knives, at first with iron handles, began to be made. Their inventor is one of those unknown benefactors whose name is omitted from the rolls of

fame. It has been suggested that as they were originally called couteaux- a name found in use down to a late period [*note: Wilson Joseph, cuttoe and pen knife cutler, Castlefold- 1774]

-the device came from France. At first spring-knives were but clumsy, and made with only one blade..."

Transcriptions of testimony from the Old Bailey for the murder trial of William Chetwynd, who was Charged with the the Murder of Thomas Ricketts, 12th October 1743; show that this confusing term was also problematic during the eighteenth-century:

"Hamilton. It was a Sort of a French Knife.

Council. Was it a Penknife? Or what Knife was it?

Hamilton. It was a pretty large Knife.

Council. Was it a Clasp Knife? Hamilton. Yes."

further on in the trial:

"Council. I think, Sir, you were telling the Court of a French Knife;

I own I don't know what they are; but the Question I would ask you, is,

whether most of you young Gentlemen do not carry these Knives in your Pockets?

Hamilton. I have heard so; it was a Knife that he always had."

Council. What kind of a Knife was it?

Humphreys. It was a Knife with a long Handle.

Council. Was it a long Blade?

Humphreys. It was such a Blade as this; this is but a Piece of it.

Council. It is a French Couteau.

Prisoner's Council. It is no such Thing, it is only a common French Knife."

Common French clasp knives of the period generally lacked springs, and were simple blades that folded into a boxwood or horn handles (for further reading on these, see Gladysz and Hamilton's excellent Journal of the Early Americas articles).

French folding knife image from Jean Jacques Perret's L'Art du Coutelier ca. 1771

Several examples survive, many complete with French maker's marks on their blades and at times their handles.

To make deciphering this commodity even more difficult, a variety of short swords known as cutteau de Chasse (literally hunting knife) are in contemporary circulation.

"Lancaster, March 8, 1778. WAS FOUND the 7th instant, and left in the care of Mr. William Atlee in Lancaster, a neat hanger, or cutteau de chasse , which is supposed to belong to some Gentleman of the Army. If the owner of it will apply to Mr. Atlee it will be delivered to him, on paying the charges of this advertisement, and some small gratuity promised by Mr. Atlee to the finder. " (The Pennsylvania Gazette)

When available to the modern scholar, the price (the short sword "cuttoes" being significantly more expensive than cuttoe knives) and context can help decipher which of the two is being discussed

in period documents.

Returning to our cuttoe knives, how can we be sure they were "clasp" or "spring" folding knives as described in the Sheffield references and Chetwynd case above?

Thankfully advertisements and receipts with a few tantalizing details help confirm this. The receipt below implies that Cuttoes are in fact 'spring' or folding knives.

Philadelphia, " William West for accot: General Forbes Bot: of Jeremiah Warder. "

Docket: "No. 17 Jera. Warder" Box 3 1758 May 8 Ms, 2 p.

Papers of John Forbes, MSS 10034, Tracy W. McGregor Library of American History,

Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia

Philada: 5 March 8th: 1758

William West for Acco: General Forbes...Bot: of Jerimiah Warden...

6 doz: Black Spring Knives -7/

9 doz: Cuttoe ....ditto -7/

23 doz: do: Larger ...do 7/6

2 doz: Very large ...15/

Other advertisements are even less vague:

"Just Imported in the last Ships from LONDON BRISTOL , &c. By Edward Blanchard, And to be sold at his Shop in Union - Street...by wholesale or retail, cheap for Cash......cutteau and all other sorts of clasp knives...."

( Boston Evening-Post, published as The BOSTON Evening-Post.; Date: 06-23-1760; Issue: 1295; Page: [4];)

"At the Store over Mr. John Dupee's...to be SOLD by Nathaniel Williams...spring Knives & Cutteau ditto, Penknives..."

(Boston News-Letter, published as SUPPLEMENT to The BOSTON News-Letter, and NEW-ENGLAND Chronicle.; Date: 03-25-1762; Issue: 3013; Page: [4]; Location: Boston, Massachusetts)

"pistol capt and cutteau pocket knives; Barlow penknives..."

(Pennsylvania Chronicle, published as The Pennsylvania Chronicle, and Universal Advertiser; Date: From Monday, May 2, to Monday, May 9, 1768; Volume: II; Issue: 15; Page: 117; Location: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania )

Sketchley's Sheffield Directory of 1774 lists only three specific makers of "cuttoe" knives; a modern rendering of those marks appears below.

"Gillot William, ditto [spring knife] & cuttoe at ditto [Heely near Sheffield]" p. 4.

-[dagger pointing left] SYNO

"Waterhouse Jeremiah, table knife and cuttoe cutler, Scotland." p. 11.

* [Maltese Cross]

O

A

"Wilson, Joseph, cuttoe and pen-knife cutler, Castlefold." p. 12.

Y.NOT

Pictured below is a ca 1770 bone handled English "clasp", or "pocket" knife, most likely also termed a "cuttoe" in the 18th-century from a private collection. It is marked (detail at right) to Jeremiah Waterhouse, a Sheffield "table knife and cuttoe cutler" who worked on Scotland Street.

1781 Patent for Cutteau Scales London Gazette 1783:

"The Commissioners in a Commission of Bankrupt... proceed to the Sale of Two Third Parts of Certain Letters Patent under the Great Seal of Great Britain, dated the 21st of February, 1781, whereby His Majesty gave and granted to James Reaves, of Chesterfield in the County of Derby, Cutler, sole Privilege, during the Term of Fourteen years, of making and vending his new invented Table-Fork-Blades, both Scale and Round Tongues, with two, three or more Prongs; also Spring Knive Scales, commonly called Cutteau or Pocket Knive Scales of various Sorts, made of Cast Metal called Pig Iron, either entirely of the Metal, or intermixed with Steel or oth[e]r Metal or Metals, which, by a new preperation of tempering the several Articles, renders them sufficiently strong and elastick for every Purpose to which the same may be applied..."

In this 1809 reference, what is clearly the handle of a folding knife is described as the "scales". These are subsequently referred to as "handles" being "covered" with horn, etc.

"Penknives. The manufacture of penknives is divided into three departments, the first is the forging of the blades, the spring, and the iron scales; the second, the grinding and polishing of the blades; and the third, handling, which consists in fitting up all the parts and finishing the knife. The blades are made of the best cast steel, and hardened and tempered to about the same degree with that of razors. In grinding they are made a little more concave on one side than the other; in other ways they are treated in a similar way to razors. The handles are covered with horn, ivory, and sometimes wood, but the most durable are those of stag-horn. The most general fault in penknives is that of being too soft. The temper ought to be not higher then a straw colour, as it seldom happens that a penknife is so hard as to snap on the edge."

By 1787 over a hundred specialized "Couteaux" makers were listed in the Sheffield directory; cutlers are listed under the heading of the wares they produce.

"Common Pocket and Penknives. Manufacturers in Sheffield."___30.

"Manufacturers in the Neighbourhood.

Note. Those who make Penknives, have the Word Pen put against their Names; the others make only Couteaux."

11 are marked "Pen," with 107 making "couteaux" of a grand total of 148.

(A Directory of Sheffield; Including the Manufacturers of the Adjacent Villages." Gales and Martin, Sheffield, G. G. & J. Robinson, London. 1787.)

Cuttoe knives came in a variety of sizes and materials (including "pistol cap'd", stag, horn, bone handles and etc).

Table of Goods and prices for the Indian Trade

Charles Town in South Carolina, July 19th, 1762

Knives,

common Clasp 2---1 [pounds of skins]

[The "common" clasp knife in the list below may be a French style clasp knife lacking a spring]

small Cutteaus 2---1 [pounds of skins]

larger Cutteau 1---1 [pounds of skins]

largest Cutteau 1---2 [pounds of skins]

(Colonial Records of SC/Documents relating to Indian Affairs 1754-1765 William L. McDowell, JRUSC Press, Columbia SC 1970 p566-569)

Several very large specimens survive, and a description of "a riot among a gang of wheel-barrow felons" in Rhode Island from the The Pennsylvania Gazette. May 23, 1787 mentions "A woman of infamous character was seized, and, on searching her, a cutteau knife , about 16 inches long, sharp pointed, was found concealed in her bosom".

Cuttoes knives may have proven popular items for the Indian trade as they might were thought as less liable to be used in an offensive manner than fixed blade "butcher" or "scalping" knives.

In 1765 Robert Callendar’s Indian goods laden pack train was attacked by

'Cumberland County men' in the belief that it contained offensive weapons such as scalping knives. Merchant Thomas Wharton rebuffed this, and stated that

he was "satisfied, that no Other than the Common Cutteau Knives were sent; which Knives are well known in England, And are Used by most Farmers in this province..." p. 201.

[Citing Thomas Wharton to Franklin, 25 March 1765, PBF 12: 95. The Papers of Benjamin Franklin (New Haven, 1959), 3: 214-16. Hereafter cited as PBF.]

Although rare in period images and often referred to in somewhat mysterious terminology; the common English clasp knife and the "cuttoe" knife appear to be one and the same. For an archaeological specimen from 1775, see the James Birmingham grave from 96 in South Carolina.

Tuesday, February 5, 2013

OSFP Errata

As any author will tell you, there are always a few minor (and at times not so minor) errors that show up after publication. Sadly, I have not been immune to this and the errors I am aware of are listed below.

Sincerely and with apologies,

Jim

page 77

Caption at top right should read "American rifle featuring American, Dutch and or possibly English and German components." There is a pistol signed “J. Depre Maastricht” in the Visser collection (cat.312) that points to a Dutch origin for the lock at least.

page 85

Buccaneer muskets of British origin and unique aesthetics certainly existed, and the text should reflect the possibility of an English buccaneer style gun in that context. The gun pictured may be an Anglo restocking of earlier French parts.

page 131

Letter from Peter Schuyler to William Shirley should be in the New Jersey section, not that of New York.

page 165

Benjamin Rogers horn. Although there was a Virginia Provincial Soldier named Benjamin Rogers, information in the form of a very similar horn (inscribed Freeborn Hamilton most likely a man from Kent County, Rhode Island) has come to light since publication. The stylistic similarities point towards both horns originating from the same hand. The attribution originally published seems to be incorrect, and barring further information the Rogers horn is likely a Rhode Island piece.

Wednesday, January 16, 2013

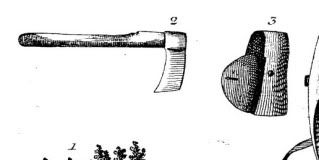

"A rough case for his tomahock..."

One of the items that frequently pops up in interwebz discussions is a hatchet/tomahawk cover or case. In the 18th century, it seems to have been fairly common to use a small hatchet simply thrust in the belt or perhaps hanging off the shot bag strap (see Verger's rifleman) with the edge unprotected.

In the Pension Application of Simeon Buford he mentions that he "wore a Belt to carry his hatchett, which had a brass buckle on it, which had inscribed on it “21 Regiment.”

Thankfully, some people in the period did use a cover so those who feel compelled to use one have something to go on.

from Knox, John D. (Doughty, Arthur G. Ed.) An historical journal of the campaigns in North America for the years 1757, 1758 and 1760 Volumes I-III, Toronto Canada, Champlain Society, 1914-1916

p352 1759

"His knapsack is carried very high between his shoulders, and is fastened with a strap of web over his shoulder, as the Indians carry their pack. His cartouch-box hangs under his arm on the left side, slung with a leathern strap; and his horn under the other arm on the right, hanging by a narrower web than that used for his knapsack; his canteen down his back, under his knapsack, and covered with cloth; he has a rough case for his tomahock, with a button; and it hangs in a leather sling down his side, like a hanger, between his coat and waistcoat."

As the images below will show, there are several forms and ways of doing these in the 18th and early 19th centuries.

Isaac Shelby's hatchet and cover:

Alexander MacKenzie

1767 Huntsman's rig

Farrier, 11th Dragoons by Morier ca 1750

German Military ca 1783 from "Was ist oficier..." (for originals see Burg Forchtestine):

and a French example from La Porterie ca 1754:

Arthur Wentworth of Bulmer, near Castle Howard, Yorkshire 1767

In the Pension Application of Simeon Buford he mentions that he "wore a Belt to carry his hatchett, which had a brass buckle on it, which had inscribed on it “21 Regiment.”

Thankfully, some people in the period did use a cover so those who feel compelled to use one have something to go on.

from Knox, John D. (Doughty, Arthur G. Ed.) An historical journal of the campaigns in North America for the years 1757, 1758 and 1760 Volumes I-III, Toronto Canada, Champlain Society, 1914-1916

p352 1759

"His knapsack is carried very high between his shoulders, and is fastened with a strap of web over his shoulder, as the Indians carry their pack. His cartouch-box hangs under his arm on the left side, slung with a leathern strap; and his horn under the other arm on the right, hanging by a narrower web than that used for his knapsack; his canteen down his back, under his knapsack, and covered with cloth; he has a rough case for his tomahock, with a button; and it hangs in a leather sling down his side, like a hanger, between his coat and waistcoat."

As the images below will show, there are several forms and ways of doing these in the 18th and early 19th centuries.

Isaac Shelby's hatchet and cover:

Alexander MacKenzie

1767 Huntsman's rig

Farrier, 11th Dragoons by Morier ca 1750

German Military ca 1783 from "Was ist oficier..." (for originals see Burg Forchtestine):

and a French example from La Porterie ca 1754:

Arthur Wentworth of Bulmer, near Castle Howard, Yorkshire 1767

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)